Common law marriage "myth"

Last verified: November 2025 – England & Wales.

You may own a home together, share bills, raise children and be seen by everyone around you as a committed couple. Friends and family talk about you as “basically married”.

The law does not.

If you and your partner are unmarried or have not entered a civil partnership, the intestacy rules (i.e., not having a Will) are not your friend. Intestacy does not recognise these relationships, so your partner will receive no benefit from your estate. The concept of “common law marriage” is only a myth and has no legal basis. In the eyes of the law, you could have met online yesterday.

Living together as a couple for any length of time does not grant you the legal status of “common law spouses”. If you are not married or in a civil partnership, you have no automatic right to inherit from your partner’s estate if they die without leaving a Will.

To avoid confusion, a cohabiting couple is two people who choose to live together outside marriage or a civil partnership, and who are in a relationship.

Rights under the law

The rules of inheritance are clear. If you live with your partner but are not married or in a civil partnership, you have no automatic entitlement to your partner’s property or assets on death. The position is no different, even if you have children together. In essence, the law favours married couples and civil partners. If you are unmarried, the surviving partner receives nothing under the intestacy rules.

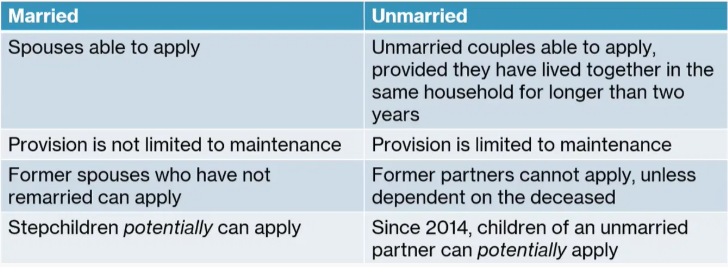

If an unmarried partner’s significant other dies without a Will, they may be able to apply for financial provision under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 (“the 1975 Act”). A cohabiting partner can apply if they lived in the same household as the deceased person for at least 2 years immediately before death, as if they were spouses or civil partners.

Former partners cannot apply under the “cohabitant” route in the 1975 Act as former spouses can. Their only potential route is as a dependant of the deceased under s1(1)(e). This also applies to any children if they were treated by the deceased as a child of the family. Until 2014, this only covered step-children.

Even where the court does make an award for a married survivor, the courts may decide to treat the claim in a similar way to a divorce, making an award closer to what they would have received on separation rather than on death.

For unmarried couples, any award is more likely to be focused on maintenance and basic needs than on preserving a long-term inheritance.

A brief overview of the 1975 Act

The 1975 Act allows certain categories of people – including spouses, civil partners, former spouses in some cases, children and qualifying cohabitants – to ask the court for “reasonable financial provision” from an estate where the Will or intestacy rules do not provide it.

It does not give a surviving partner an automatic share of the estate. Instead, it gives them the right to ask the court to step in, which is usually stressful, slow and expensive compared with having a clear Will in place.

Why a Will matters for cohabiting couples

If you are cohabiting with your partner and want to make sure they inherit from your estate, you should make a Will that clearly sets out what you want to happen.

If you jointly own a property with a partner and this is registered at the Land Registry, you are entitled to your share of that property. How that share passes on death will depend on how you own it (for example, as “joint tenants” or “tenants in common”) and what your Will says.

Funerals

Equally distressing can be the position on funeral arrangements. Without a Will, an unmarried partner has no automatic rights to decide funeral arrangements or even what happens to the body or ashes.

If no close family members are available or willing to be involved, the Local Authority in which the person died (not where they lived) is responsible for arranging the funeral and the disposal of the body under s.46 of the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984.

Parental responsibility (PR) and guardianship

Parental responsibility (PR) is defined as “all the rights, duties and authority which, by law, a parent of a child has in relation to the child and their property” (s31 Children Act 1989). This grants the power to make crucial decisions concerning a child.

Only individuals with PR can appoint guardians in a Will (see the Guardianship article for more information). If you are cohabiting and have children together, it is essential to understand who holds PR and who would be appointed as guardians if something happened to you.

Tax

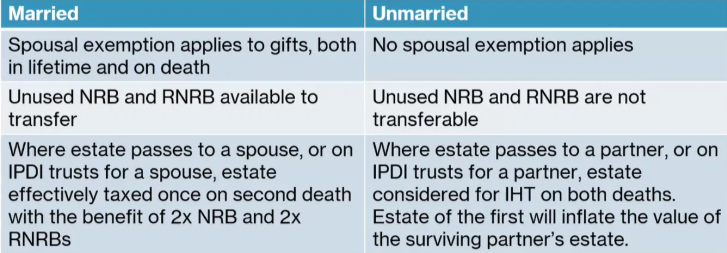

Married couples and civil partners have an unlimited inheritance tax allowance between themselves. All other couples do not.

Therefore, if an unmarried person leaves more than the Inheritance Tax (IHT) Nil Rate Band (NRB) allowance – currently £325,000 – to anyone other than a spouse or civil partner, the excess will usually be taxed at 40%. These figures are subject to the current tax regime; allowances and rates can change, and asset values can rise, so it is essential to review this from time to time.

Summary of the tax differences

In simple terms, married couples and civil partners can usually pass everything to each other on death without an immediate IHT bill and can often combine their IHT allowances. Unmarried couples do not have these automatic protections. That gap is where careful planning, including the use of trusts in the right circumstances, can help.

Trust planning for unmarried couples

One effective way to reduce the 40% liability is to use a trust. Various types of trusts are available, but those with a discretionary trust (DT) element are often the most suitable in this context. While a separate article is dedicated to discretionary trusts, here is a summary.

On first death, you can place up to the equivalent of the Nil Rate Band into a trust – currently £325,000 – which is IHT-exempt at that point. In effect, you can give your trust (standing in for your “partner”) up to £325,000 without incurring inheritance tax, which can save up to £130,000 at current rates.

For some trusts, there may be setup, entry, anniversary, income, and exit charges. These need to be weighed against the potential IHT savings and the flexibility gained.

Notes on the Residence Nil Rate Band (RNRB)

For married couples, step-children are treated as direct descendants and can qualify for the Residence Nil Rate Band (RNRB). Children of unmarried partners do not benefit from this in the same way, which is another example of the law favouring marriage and civil partnership.

Trust options for unmarried couples

There is no single perfect trust solution for unmarried couples. Life interest and flexible life interest trusts can be less advantageous, because they may be taxed on both the first and second death, rather than only on the second death, as is often the case for married couples. They can still have their uses, but often a better-fitting structure is available.

Discretionary trusts are often more advantageous.

A Property Protection Trust and other discretionary trusts can allow a partner to remain living in the property rent-free. After the second partner’s death, the property can then be distributed to their children or other chosen beneficiaries. The trust is treated as having inherited the property on the first partner’s death, which helps prevent the surviving partner’s personal estate from increasing as much. This can better utilise the available Nil Rate Band allowances.

Exit and anniversary charges for discretionary trusts are technical and need specialist advice. Still, typically the maximum charge will be 5.85% for exit charges and 6% for 10th anniversary charges on amounts above the Nil Rate Band in force at the time.

Exceptions and complications

It is often said there is an exception for every rule, and sometimes those exceptions make a bad situation worse.

Banfield v Campbell [2018]

Mrs Campbell left £5,000 to her “friend,” Mr Banfield, and the family home and everything else to her son, James, on his 25th birthday. She did not update her Will for several years.

Mrs Campbell left £5,000 to her “friend,” Mr Banfield, and the family home and everything else to her son, James, on his 25th birthday. She did not update her Will for several years.

On a flight back from the Canary Islands, Mrs Campbell died. James and other witnesses claimed Mr Banfield was like a lodger who slept in a separate room. He did not pay rent; Mrs Campbell did not wish to live alone.

Not satisfied with £5,000, Mr Banfield challenged the Will. He argued that he was a financially dependent cohabitant and could not afford his own home. The judge agreed that some provision should be made for him and ordered that he receive a maintenance allowance.

Mr Banfield then argued that this was not enough. The judge ordered the home sold, and Mr Banfield was given a life interest in half the sale proceeds. The other half went to the son, who had always been the primary intended beneficiary of the Will.

The case illustrates how outdated Wills and unclear intentions can lead to conflict, delay and expense, and can dramatically change who ends up benefiting.

Care-home fees and cohabiting partners

If a property owner goes into care, their home may be disregarded for the means test if an unmarried partner or another relative lives there as their sole or primary residence. However, councils have discretionary powers to consider “all relevant factors”. If they believe the main reason for the arrangement is to preserve a family inheritance or avoid selling the property, they may decide not to disregard it.

For most clients who consider trust and inheritance planning, there is no reasonable expectation that they will need care, and it is not their primary concern; any impact on care fees assessments is usually a potential side-benefit of the main planning reasons, not the driving force.

These examples highlight the importance of keeping your planning current and regularly reviewing your Wills as relationships and living arrangements evolve.

Bringing it all together – protecting each other and your children

For cohabiting couples, the “common law marriage” myth can be actively harmful. It can lull people into a false sense of security at the very time they need clear, written protection most.

Making a Will, reviewing how you own your home, understanding who has parental responsibility, and considering trust planning where appropriate can all help to:• protect a surviving partner from hardship

• provide fairly for children from this and any previous relationships

• reduce unnecessary inheritance tax where possible under the current rules

• avoid disputes that drain time, money and emotional energy from the people you care about.

If you are living together without being married or in a civil partnership, the safest position is not to rely on the myth of common law marriage. Get proper advice, put a Will in place and review it as life changes so that the law reflects your real intentions, rather than leaving it to chance.